Pamplona to Logroño, 26th March – 1st April 2007

The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy has a few things to say on the subject of towels…

A towel, it says, is about the most massively useful thing an interstellar hitchhiker can have. Partly it has great practical value – you can wrap it around you for warmth as you bound across the cold moons of Jaglan Beta; you can lie on it on the brilliant marble-sanded beaches of Santraginus V, inhaling the heady sea vapours; you can sleep under it beneath the stars which shine so redly on the desert world of Kakrafoon; use it to sail a mini raft down the slow heavy river Moth; wet it for use in hand-to- hand-combat; wrap it round your head to ward off noxious fumes or to avoid the gaze of the Ravenous Bugblatter Beast of Traal (a mindboggingly stupid animal, it assumes that if you can’t see it, it can’t see you – daft as a bush, but very ravenous); you can wave your towel in emergencies as a distress signal, and of course dry yourself off with it if it still seems to be clean enough. – The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams.

The Larrasoaña refugio had been almost full; we resolved to make a good start the next morning. When we left it was still dark. (It must be noted, however, that the clocks had just gone forward, so this was not entirely due to extreme keenness on our part.) We were well down below the snowline by now, and made good progress almost as far as Villava, until we took a wrong turn across a muddy field and ended up having to climb over a wire fence. Once we had got ourselves back on the right track we found ourselves looking down on the motorway, and felt rather superior to the cars and lorries heading towards Pamplona. Pilgrims had been going that way for over a thousand years. We were there first.

We tramped on past the Trinidad de Arre church and refugio, through Villava, alongside a stream, and through the Portal de Francia into Pamplona. Pamplona, of course, is where the famous Bull Run happens, but we were three months too early and not overly bothered. Upon reaching the centre of the city I was afflicted by an intense reluctance to make any decisions, so Anne took charge and settled that we would eat lunch at Bar Iruña, a vast, mirror-lined establishment with a certain decayed glamour. The atmosphere seemed familiar; by the end of our (three-course) lunch we had pinned it down. It was very similar to the Imperial Hotel, the J. D. Wetherspoon’s pub in Exeter. The cheap food, the battered, once-lavish décor, the sense of having gently come down in the world, all were reminiscent of the Imp. Bar Iruña was a favourite haunt of Hemingway’s, according to the menu. Fair enough.

It was after lunch that things started going seriously wrong. First Anne’s debit card was rejected by two separate cash machines, then we failed to find a post office. We did manage to find a souvenir shop, where we purchased such essentials as postcards, and the best fabric badge of my entire collection, and a chemist, where we were able to buy ‘Hansaplast’, the Spanish equivalent of Compeed. We began to make our way out of the city. The weather, having been dull and grey all morning, suddenly turned sunny. Anne’s blisters were seriously painful now; I was getting a headache and beginning to be irrationally worried that the refugios in Cizur Menor, the next village, would be full before we got there. We sat down on a bank on the west side of the university for Anne to inspect her feet. One of the blisters had burst; she applied Compeed. This, we learned later, was a serious mistake.

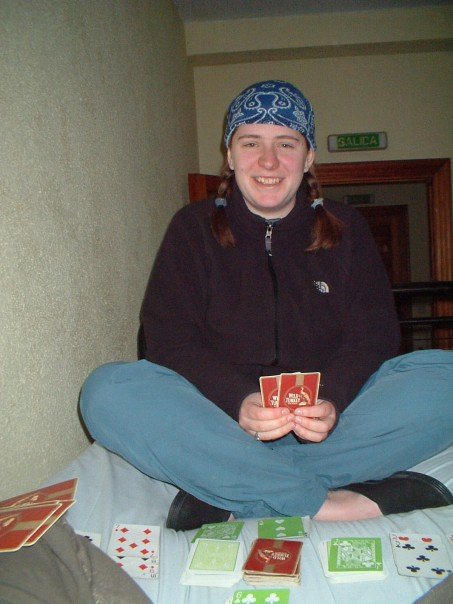

We made it, however, to the Roncal refugio in Cizur Menor, where there was plenty of space both in the dormitories and on the drying racks. We also found Brantz, who had indeed pushed on to Zubiri the day we had stopped at Viskarret and regretted it; he had got very cold and his knees were giving him problems. He had been obliged to take a rest day in Pamplona. The refugio catered to every conceivable pilgrim whim: it had a kitchen, a common room with TV and internet station, and even a vending machine selling everything from cans of San Miguel to vacuum packed olives. The sun was still flooding the courtyard. Regardless of the fact that it was now pushing 4pm, we did our laundry and hung it out to dry. I tried toasting the little bread rolls called pan de leche in an attempt to make them more interesting. Whether I succeeded depends on how interesting one finds carbon, really. I certainly succeeded in toasting them. Meanwhile, Anne watched the TV, which seemed mostly to be showing a commercial for facial lotion, advertised for some bizarre reason with shots of snails slithering over leaves. By the time I worked out the machine to my own satisfaction I had wasted a lot of bread, but it was edible eaten with spreadable processed cheese, and olives from the vending machine livened things up no end.

The lady who signed us in and stamped our credenciales had told us that there would be Mass at the village church at 7.30pm, so we wandered up there with a few minutes to spare beforehand. We sat there for quite a long time waiting for something to happen. Several children of varying ages got up and disappeared into what we assumed was the vestry; then they came back again. Some older members of the congregation got up to do what we assumed were confessions. At around eight o’clock we gave up and went back to the refugio. We then abandoned our high principles and used the internet machine to send an email detailing the debit card fiasco to Anne’s parents. It was agreed that it was probably just the card being temperamental, as it had been before we left, but that her parents would be prepared to transfer some money into my account if necessary. With that settled, we went to bed, first checking on the laundry, which had predictably enough failed to dry. We draped it around our beds and hoped for the best.

The next morning it was as grey and drizzly as if the previous afternoon’s sun had never happened. The laundry was still not dry; Anne’s towel was, in fact, still sopping. I opened a tin of sardines in tomato for breakfast and managed to get oily tomato all down the front of my waterproof, where it remained for the duration of the trip. Matters did not improve much once we started walking. The drizzle became rain. The rain was wet and getting wetter. So were we. I was again getting wetter than Anne because I had no waterproof trousers. I was wet; I was cold; I just wanted to stop. My diary says succinctly ‘Ascent to Zeriquiegui hellish.’ When we reached that village we joined a flock of other pilgrims, ponchoed and dripping, under a kind of veranda affair. It seemed to be the exterior of a pilgrim centre that was still under construction, but it provided some degree of shelter. We nibbled biscuits, and I persuaded Anne that we should stop at the next refugio, because it was so cold and miserable.

That was the low point of the day, however, and our spirits rose along with our altitude as we approached the Alto de Perdón. The mist was thick here, and we came across a miniature landslip, a few last streaks of snow, and a lot of water. Things were improving none the less. We were amused when, nearing the top, we looked up and realised that we were standing directly underneath a wind turbine. The thing was so quiet compared to the wind itself and so completely veiled in fog that we would never have seen it had we not stopped. At the very top stands a line of silhouettes cut from sheet metal representing pilgrims from medieval times to the present day; they are much larger than life and looked very dramatic against the swirling mist. We did not stay long to admire them, however; the wind was uncomfortably strong, and we began the descent. We passed several little cairns of stones. We added to the first one, but after that found them increasingly irritating. The most pointless sort, we thought, were the ones that had been begun on top of concrete waymarkings: any more than seven or eight medium-sized stones and they would start falling off. Sometimes, when we were feeling particularly wicked, we would push the stones off ourselves.

We were heading downhill towards Uterga, which was the first village listed in the guidebook as having a refugio. Here, I had insisted, we would stop. However, as with Valcarlos, and Burguete, and Espinal, when we got there we simply didn’t feel like it. We did stop at one of the two refugios, because it also sold coffee and doubled as a pilgrim souvenir shop. I sat near the radiator, drinking coffee, and steamed gently. Anne bought a sunhat embellished with a camino shell (a yellow, stylised affair, much like what would happen if one crossed the Shell Oil symbol with a comb) despite the awful weather, on the grounds that she would be sure to need it sooner or later. Then we pressed on through Muruzábal and Obanos to Puente la Reina. There was a recommended detour to look at a 12th century church in Eunate, but we felt it was not worth it, given the conditions. We plodded on through the rain.

Puente la Reina was, historically, the site where the two routes over the Pyrenees met. It was also the place of our first real rest day, the first time we saw storks, managed to buy stamps, melted my boots, and learned the hard way about just how temperamental refugio laundry facilities could be. The refugio in question was attached to the monastery of the Padres Reparadores, and consisted of two rooms of bunk beds, another containing two showers, two lavatories, a sink and a tumble dryer, and a dining room with benches and an open fire.

Pilgrims who had arrived before us had already taken advantage of this last, and had arranged their boots in pairs in front of it to dry out. We did likewise. This, as it turned out, was not the most sensible idea. Nor was assuming that the tumble dryer would work well enough to dry all our clothes adequately, and washing them, and then discovering that it wouldn’t. As a result, I discovered a new use for my towel. I had already wrapped myself up in it against the cold, not of the moons of Jaglan Beta, but of snowy Viskarret, and later it would serve very nicely as part of an improvised icepack, but for now, fastened with a couple of safety pins, it made a passable skirt. Once again I had no dry trousers.

We went out (in the rain) for dinner; Bar La Plaza had a pilgrim menu for €8.90, helpfully advertised in four languages. Despite the fact that I was wearing that most unpilgrimlike of garments, a skirt, we were handed this menu without question, and made a good meal from it. Anne’s blisters were particularly troublesome by now, and she took one of her poles out with her to use as a makeshift walking stick. When we returned to the refugio – somewhat tipsy after sharing a bottle of red wine – we found a German lady lecturing a group of footsore Koreans about the importance of proper foot care and rest days. She seized upon Anne’s foot with a kind of horrified glee, and solemnly exhibited it to her audience as an example of the state that feet should never be allowed to get to. We decided that we probably ought to take a rest day.

I had blisters too, but not on my feet. My boots had got too close to the fire, and the rubbery sealant had melted and bubbled. It did not do much to improve their appearance, but I was luckier than some. My boots merely looked slightly silly, and I found that the accident made no perceptible difference to their performance; others’ had burned right through.

We could not help feeling a little smug in the morning, seeing that it was still raining, and knowing that we did not have to walk that day. I left an explanatory note in my best Spanish for the hospitalero; we were allowed back later, so it must have worked. We took advantage of the fact that we were in a town at a sensible hour, and visited the Post Office, a café, a pharmacy and the church. (I had been to the pharmacy the previous evening, and cursed the fact that Lil-lets do not appear to exist in Spain. Attempting to work out how the hell applicator tampons work, in Spanish, and after half a bottle of red, is not recommended. In the end I pulled the thing to pieces.) There were some ladies sweeping and dusting in the church, but we said Mattins anyway. We found when we came out that it had at long last stopped raining. We returned to La Plaza for lunch, and discovered to our amusement that a meal that had been merely adequate the previous day, after a walk of eighteen kilometres, was now extremely filling. We spent the whole afternoon there, eating, drinking, writing postcards and thinking theological thoughts. The staff had either forgotten about us completely or were content to let us squat in the dining room. Eventually returning (via the supermarket) to the refugio, we saw, amid a messy nest of straggling sticks on the top of a yellow tower, our first stork.

Anne is the bird enthusiast, but I was equally excited. Perhaps it was a vague memory of reading The Wheel on the School when I was a little girl, perhaps insidious margarine marketing, perhaps an idea never quite dispelled by years of proofreading birth stories that storks bring babies, or perhaps simply the sheer exoticism of something I had never seen, either in England or elsewhere; whatever the reason, there is something special about these white and black birds with their clumsy red legs and their over-sized, gloriously chaotic nests. We must have seen getting on for a hundred storks in our progress westward, but the novelty never wore off. Storks on church towers, storks on their own dedicated poles, storks following tractors; each stork merited attention, and frequently a photograph. So attached did we become to the storks that – much further along the camino, at Villalcázar de Sirga – we took the almost unprecedented step of cluttering ourselves up with tourist junk and purchased pin badges depicting a nesting pair.

This, however, was all in the future, and for the moment we stood enthralled by the very first stork of all. Our second stork appeared a few minutes later, when we returned to the refugio; there was a nesting pair on the monastery bell-tower. We also met another interesting character: a French gentleman who had no hesitation in informing us that he had been to Santiago eight times, and producing laminated certificates to prove it. He also attempted to convince a girl with knee problems that all her troubles would be solved if only she had a European health insurance card; given that she was Australian, he was unsuccessful in this. I seemed to be the only other person in the hostel who spoke French. This meant that he frequently called upon me to interpret various gems of wisdom – to beware, for example, of the fleas in León. We, and the Australian girls, concluded that he was a bit weird.

The next morning we left Puente la Reina, crossing the Queen’s Bridge at last. We saw some more unfamiliar birds; Anne said they were black redstarts. I had no reason to disbelieve her. We climbed up towards Cirauqui; a tiring, muddy, slippery stretch, during which we discussed how amusing it would be if Captain Jack (of Doctor Who fame) turned out to be the Master – a speculation that had been entirely Jossed by the time we got back to Blighty, but none the less diverting for that. Cirauqui itself was a pleasant enough place, cascading down from the top of the hill. I was excited to discover a Calle Santa Catalina; this was before I worked out that Catalina was what every Spanish Catherine was called. We crossed a Roman bridge to leave the village; shortly after this one of my telescopic walking poles telescoped and refused to remain untelescoped for some considerable time. The camino was then diverted around a section of motorway, which was confusing, and probably longer than it would otherwise have been. We lunched in Lorca, drank lemonade in Villatuerta, and arrived at last in Estella after an uncomfortable stretch of concreted road.

I spent part of the evening wandering around Estella (an attractive town of narrow streets and old buildings) searching for some new underwear. I succeeded… sort of. I managed to get extra-large child-size knickers, which fitted, but not very comfortably. We found M. Huit Fois à Santiago again; he had also made it to Estella and was staying at the refugio. We avoided him. An Australian couple, Terry and Marg, were more promising acquaintances.

A highlight for many pilgrims on the road out of Estella is the wine fountain at Irache. We stopped there, and I drank a token quarter of an inch of wine from a plastic mug. It was, after all, early in the day, and we had a long way to walk. We also wanted to visit the adjacent monastery, which was not yet open, so we sat on a bench outside and said Matins. We did the visit and got the sello. Then we moved on, climbing up slopes occupied mainly by dormant vineyards to Villamayor de Monjardin, where we had hoped to be able to buy lunch. Nothing was open. Not the refugio, not the other refugio, not the bar. We cursed and headed down the hill again. We were not looking forward to the afternoon’s walk; Heloise had described the section approaching Los Arcos (where we intended to spend the night) as ‘no shade, hard walk’. As we approached the bottom of the hill we saw a cheering notice. It suggested the possibility of food, and drink, and only a slight detour from the path. We decided to follow the detour.

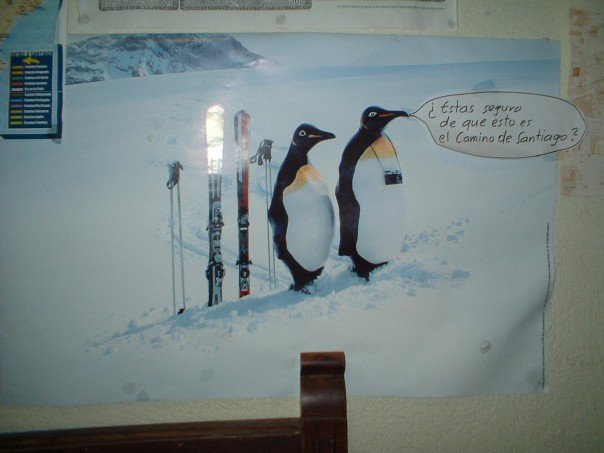

After a very satisfactory lunch, the proprietor of the bar directed us back to the camino with the help of an aerial photograph, and we set out on what turned out, despite all our misgivings, to be a very pleasant afternoon’s walk. We wandered, singing, through fields and vineyards, through a marshy green area noisy with the croaking of frogs (I spent some time looking for them, but only ever saw the splash that indicated where they had been a second before), to Los Arcos. It was nowhere near as arduous as we had been expecting it to be; in fact, it felt like a gentle stroll. We signed ourselves into the Albergue de la Fuente, Casa de Austria, with no problems. It was a laid-back, hippyish kind of place on three floors. It had a well-stocked bookcase (containing, to Anne’s delight, a paperback copy of The Two Towers, and a poster of a pair of penguins with the caption: ‘Estas seguro de que esto es el Camino de Santiago?’ We approved.

After a meal of pasta and tomato sauce (accompanied by red wine; I was perhaps excessively proud of myself for having opened the bottle with the corkscrew on my penknife) we went out to the pilgrim mass at the church of Santa María – a terrifyingly gilded edifice with a larger than normal population of cherubs. We were accompanied by Marg, and Ursula, an Austrian pilgrim who had begun walking with her and Terry; later we got to know all three well. I believe that this was the first point where Anne as I, as Anglicans, started to feel somewhat excluded from the mass; there seemed to be very little for us to join in with. During the distribution a hymn was sung. I recognised the tune; it was Nearer, my God, to thee, so I sang that. As pilgrims, we were all called forward to be blessed at the end of the service, and received a small prayer card with a photo of the church’s statue of Saint James. I reproduce the prayer here:

Lord, you who recalled your servant Abraham out of the town Ur in Chaldea and who watched over him during all his wanderings; you who guided the jewish people through the desert; we also query to watch your present servants, who for love for your name, make a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela.

Be for us,

a companion on our journey

the guide on our intersections

the strengthening during fatigue

the fortress in danger

the resource on our itinerary

the shadow in our heat

the light in our darkness

the consolation during dejection

and the power of our intention

so that we, under your guidance, safely and unhurt, may reach the end of our journey and strengthened with gratitude and power, secure and filled with happiness, may join our home.

For Jesus Christ, Our Lord. Amen.

Apostle James, pray for us.

Holy Virgin, pray for us.

We giggled over it a little – but later. Later still we worked out a better approximation. Marg, who had been into the church earlier in the day, led us into the cloister to show us the floats that had been assembled ready for the Holy Week processions – life size models depicting the Last Supper, the Crucifixion… It was, unfortunately, too dark to have a proper look at them, but we saw another set at Santo Domingo de Calzada, and were able to marvel at the sheer religious exhibitionism there.

It was still a fair old way to Santo Domingo, however. We left Los Arcos in golden-green morning light, and found early on that we had problems. I lost my faithful blue hanky, which annoyed me slightly, but that was but a minor irritation. We stopped in San Sol so that Anne could examine her feet. They were not pretty. She rearranged her elaborate system of wadding and cushioning and soldiered on. We stopped again in Torres del Rio. I have had a postcard of the ceiling of the church in Torres del Rio blu-tacked to my bedroom wall almost since Heloise sent it back in 2000; it is an intriguing octagonal shape. It was one of the things I had assumed I would see somewhere along the Camino. The church was locked, however, and although the guide book directed us to a certain house where the key could be obtained neither of us was in a mood to do so. We passed it by – once Anne had applied more Compeed.

Anne limped on bravely to Viana, which made it a respectable 17.5km day. The refugio there provided rather daunting three-decker bunks in part of a converted monastic building. It was adjacent to some most fascinating ruins; Anne was infuriated that she could not bear to walk far enough to look at them properly. I, meanwhile, was too busy revelling in the luxury of a working washing machine and tumble drier, and wandering around the town in search of a shop that would sell bread. It was remarkably difficult. There was a market offering leather purses, strings of beads, reproduction medieval weapons and, in fact, all the heart could desire, apart from bread. Eventually I found some in a shop called Schlecker, which looked more like a chemist’s, but served the purpose. Perhaps it was some kind of health food. Six months later, in a Frankfurt branch of Schlecker, I bought my whole family Lebkuchen for Christmas. It was a useful kind of shop.

The next day – it was Palm Sunday – Anne’s feet were still dubious, so we decided that I would walk on to Logroño alone, and she would take the bus, along with our Austrian friend Ursula. I had a happy morning’s walk, mentally contrasting my solitary way with the crowds lining the streets on the way into Jerusalem, and duly noting that I was crossing from Navarra into La Rioja. I walked carefully around the edge of a flock of sheep with attendant dogs in what appeared to be a large park, and headed into the suburbs of Logroño. A woman called out as I passed, and invited me in to drink some coffee. She put a sello in my book, and then I moved on.

Anne and Ursula, meanwhile, were not progressing so well. It being Palm Sunday and, therefore, presumably a public holiday, the bus timetable was even less comprehensible than usual. They waited for a longer than reasonable period, until, finally despairing, Ursula flagged down a passing car and asked when the bus went. The driver either did not know, or knew that the bus did not go at all; she gave the pair of them a lift.

We were reunited in the church of Santiago, where we gathered up olive branches and joined in the Palm Sunday celebrations. (I stuck a sprig of olive in my hat; it stayed there for quite a long time before it dried out and fell off.) After the service the priest, recognising us as pilgrims, sought us out and led us to the parish rooms, where he showed us where to find packet soup, frozen pizza, and the wherewithal to cook them. We were most grateful – particularly Anne and Ursula, who had got cold with all the standing around. The room was adorned with a framed series of blue and white tiles depicting the life of a San Vicente, all captioned with rhyming couplets. Eventually, around mid-afternoon, we decided that it was probably time to leave, so we moved on to the refugio; I’d noted it earlier in the day.

The refugio was large, occupying several floors, and crowded. It was backed with a courtyard with a fountain, where boots were to be washed. Other than a life-size statue of a pilgrim in the stairwell, there was not much to recommend it. It was clean, and had a well-stocked kitchen, which were assets that we would have appreciated later in the pilgrimage, but, operating at capacity (it was full by 7.30 that evening, and the first refugio that we had come across that had been obliged to close) it was distinctively claustrophobic. The dormitories were packed with bunk beds; there must have been at least seventy sleeping in the same room. A vocal minority of them were children (it being the beginning of Holy Week, some people were obviously doing stages of the camino en famille), which did not make for a good night’s sleep. We wondered, nervously, if it was going to be like this all the way from here.