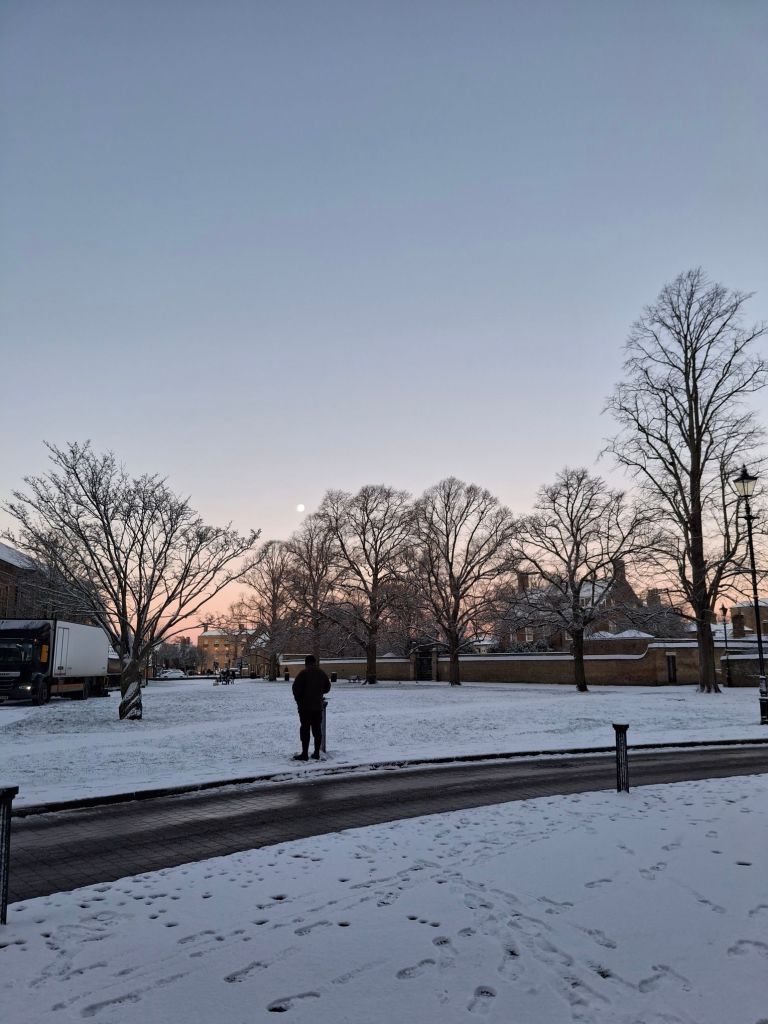

The snowdrops are out for Candlemas, as they should be. It’s been a grey, heavy, sort of a day, no shadows to be seen because there was no sunshine to cast them, so I suppose we’re plodding on into spring. The days are longer. There are buds on the trees.

A presenter on Radio 3 said earlier that Candlemas is the Christian festival of light, and, while I suppose that isn’t entirely untrue, it’s far from being the first thing that springs to mind for me. If I told you that Christmas is the celebration of the mystery of the Incarnation, I’d be correct but pedantic. But for me The Presentation of Christ in the Temple is in the same size print as Candlemas. The light is figurative, although it’s coupled with the physical light of the lengthening days. I rarely manage to get to church in the evening at all these days, so miss out on the candlelit procession which in any case was not much a feature in many of my previous churches.

For me, it’s most poignant as the hinge between Christmas and Holy Week, looking back and looking forward, prophecy and fulfilment and prophecy again. It calls back the glow and the glory, the paradox of God entering God’s world and God’s temple all but unnoticed, and it warns of the sword and the falling and rising. It picks up the disquieting note of myrrh and underscores it: this child was born to die.

Last week I was able to see these icons by Sonya Atlantova and Oleksandr Klymenko, which are on temporary display in Ely Cathedral. They’re painted on fragments of ammunition boxes recovered from battle zones of the war in Ukraine. The symbolism is obvious but no less effective for that: war and death transformed into love and beauty – but you can’t, shouldn’t, mustn’t forget it. Look at that hole where Mary’s heart is.

Loving anybody leaves you open to the certainty of grief when you have to leave them or lose them (it’s the anniversary of my father’s funeral today, too, Lord now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace); the alternative is, of course, monstrous. Parenthood makes you vulnerable, or, perhaps, aware of how vulnerable you are, how very little you can do alone to protect those who look to you for protection. Candlemas is, for me, when we understand a little more deeply what Christmas means. This child is born to die, because all of us are, and even if this birth and this death change birth and death for all of us, it isn’t going to hurt any the less.

On a lighter (ha!) note, I recall from the Journal of Saw It Somewhere Studies that jam tarts are a traditional Candlemas treat. The shape recalls the Christ Child’s cradle, apparently. This was never a part of my own tradition, but I was making chicken pie for dinner and had some pastry left over, so here we go.