You probably won’t be surprised to hear that I have been doing pretty much nothing in the way of book promotion lately. However, since I got my act together and sorted out my Draft2Digital account, I have been getting the occasional notification of the occasional sale. It’s always a pleasant surprise, a reminder that I had something to say (a decade ago in one case, my goodness) that is still saying something, and a reassurance that I still do have something to say, that it’ll bubble up to the surface in its own good time, and that someone out there will want to read it when it does.

Jae’s Sapphic Book Bingo is back for 2026, and this week’s featured square is sapphic books set in a school or academia*. Which I can very much help with. You can have Speak Its Name for undergrad, and The Real World for postgrad. You could also use The Real World for ‘Established couple’ further down the card, and, at a stretch, Speak Its Name for ‘Sapphic character involved in politics’, though I should stress it’s student politics and the involvement is not exactly voluntary. In my ‘Free Reads’ section, The Mermaid would count for the ‘Free book or free choice’ square. (It’s a short story, but Jae says explicitly that a few of those are allowed.)

Readers in the US, both Stancester books are now available through the Queer Liberation Library, along with all sorts of other good stuff. Worth a look if, very understandably, you need a distraction.

Meanwhile, I am deeply amused by Smart Bitches Trashy Books’ (not sure where the apostrophe should go, there) Unhinged Romance Bingo. I am, I think, relieved to report that none of my books fit into any of these squares, except perhaps the cycling and silversmithing in A Spoke In The Wheel for “niche business or hobby”. That said, I don’t really write romance-the-genre (ASitW is definitely the closest), so maybe it’s not really surprising. You never know, though. Maybe one day I’ll write an aggressively twee small town. In the meantime I’ll be cackling at First Name Last Name Does A Thing and Title: A Noun of Stuff and Things.

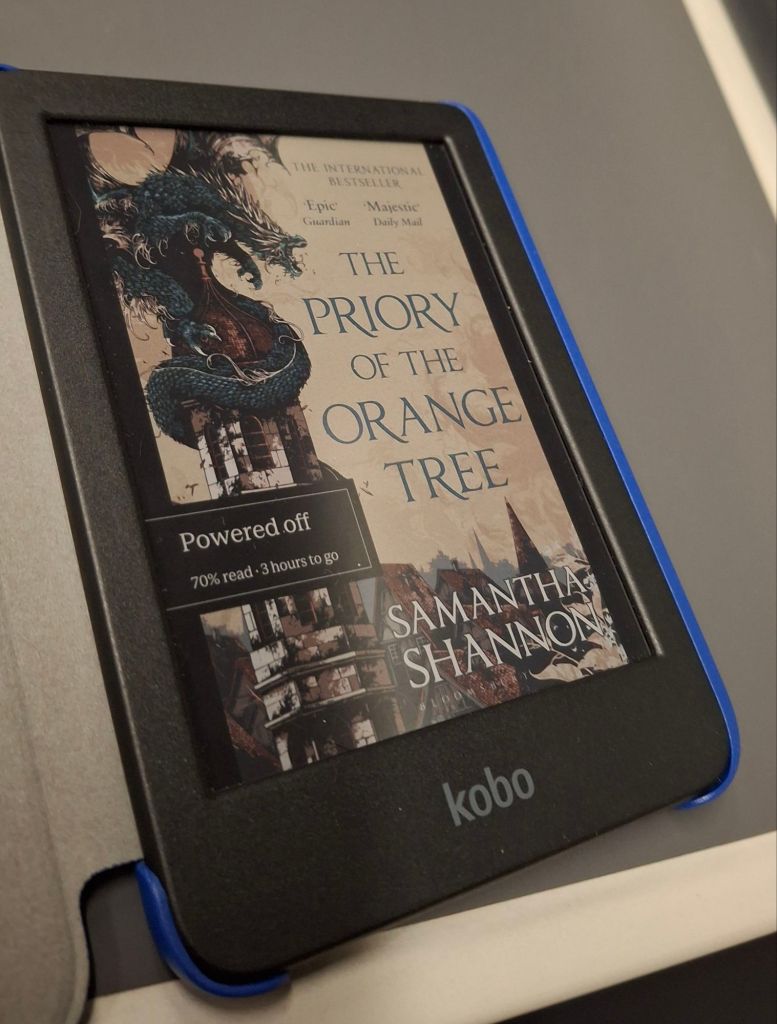

*Hence the picture. This is Cartwright Gardens, opposite the University of London’s Garden Halls.